Thursday 3 AM. Insomnia again, but this time I know exactly why. My brilliant friend is visiting me at work in a few hours and I’m having a bad case of imposter syndrome.

I am a rookie Spanish teacher. I have no Hispanic heritage. I am not a native speaker. Anna is the daughter of Cuban immigrants, a bilingual native who translates books from Spanish to English, and also speaks French, Italian, Portuguese, German, Russian, Greek, and Turkish.

Anna and I have been friends for more than 30 years, speaking exclusively in English. Today, when she visits my class, we’ll be communicating for the first time in Spanish, in front of an audience of potentially skeptical students deep in “senior spring,” their final days of high school before they leave for summer vacation, then college.

Anxious and amped, I scrawl in my journal, then open my laptop to review the plan for Anna’s visit: an essay she translated about hunger in Havana, pop songs about immigration from Latin America to the U.S., excerpts from Tell Me How It Ends, a memoir in which Valeria Luiselli advocates for undocumented migrant children seeking asylum.

Paradoxically, the plan feels like too much and not enough. Anna and I have been texting about her visit for days, but she doesn’t seem to share my urgency, which only amplifies the anxiety. Now, inspired by the 40 questions that structure Luiselli’s book, I write 40 questions for Anna as a framework for the class, then send her the file, adding a self-deprecating note about obsessiveness and insomnia.

At 5 AM, I hit the pool. As always, swimming laps helps me relax, though not entirely. I know I can’t dictate what Anna does or control how the students will react. I need to trust her, trust the students, and trust my first instinct to invite her to inspire them. This morning’s uncertainty epitomizes the thrill and the terror of teaching. You can plan a lesson all you want, but you never know how a class will go until it happens.

Invitada especial

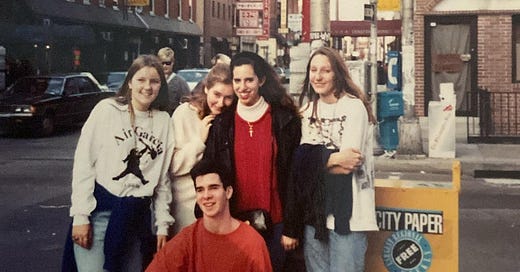

At 11 AM, fourteen teenagers hunch at desks in a circle, eating cookies. Cinnamon. Chocolate chip. Dulce de leche. I am not the kind of teacher who brings food to class, but today I bought baked goods as a bribe. While the students eat, I introduce Anna as a writer, translator, polyglot, and friend. I show slides listing the 10 languages she speaks, the 20 countries she’s visited, and the dozen books she’s translated. I show a photo of us as teenagers, the same age as the students are now, a lifetime ago. Then I yield the floor to Anna.

She begins with an etymology lesson: indigenous Taino words that conquistadors appropriated into Spanish then ultimately became English. Hamaca. Barbacoa. Huracán. Hammock. Barbecue. Hurricane.

Then she pivots to a whirlwind tour of Cuba across the centuries, from Columbus to Castro to the coronavirus. Along the way, she intersperses her own story as the daughter of Cuban immigrants. After several corporate and non-profit jobs, she found her calling: translating Cuban literature from Spanish to English.

I find her stories fascinating, but I am biased, because of my role and our friendship, and especially after my recent trip to Cuba. Still, I’m anxious about the students’ experience. Can they follow her rapid speech and the dense history or are they lost? Are they curious or bored? Are they learning anything valuable? Are they judging me for her performance? Is she judging me for their response? Was inviting Anna to class an inspired idea or a massive mistake?

Every few minutes, I interrupt Anna to echo one of her points or pose a question to the students, attempts to gauge their comprehension and aid their engagement by giving space to digest and reflect. Or maybe I’m just antsy, eager to participate and unaccustomed to relinquishing control of the classroom.

Gradually I relax, let go of the reins and expectations and let Anna do her thing. By the time she concludes her crash course in Cuba, only 10 minutes remain in class, so we open the floor to questions. One student asks if Anna feels like a different person in different languages. Another asks her opinion on the Cuban government and Cuban-American relations. And inevitably one student asks how Anna and I met.

Writing Camp

She tells them: we met at a summer camp for young writers at the University of Virginia when we were high school students.

When my mom enrolled me in that camp at age 15, it seemed like social death. I was wrong. Decades later, I’ve forgotten whatever I learned in the writing workshops. But I remember the people I met, including Anna, and how they made me feel. In school, I was a chameleon, shifting social identities, often feeling like an outsider. At camp, I belonged. Meeting creative and passionate people, I felt seen, heard, and known—joining a tribe I hadn’t known existed.

We came from different places, but had one crucial thing in common: We were all writers. Before camp, I believed that writing was solitary, private, a source of shame. After camp, I realized that writing can be social, public, and a source of pride. I’ve been learning, unlearning, and relearning that lesson ever since—and sharing it with students, clients, colleagues, and friends.

Now, more than 30 years later, Anna and I are still writers and still friends, and today were literally teaching the next generation of students.

Dim Sum debrief

After class we debrief at a nearby Chinese restaurant over soup dumplings, glazed meatballs on a bed of bok choy, and shrimp fried rice.

“See,” Anna says, triumphant. “I told you we didn’t have to plan all those activities.”

She’s right. The class wasn’t exactly what I had originally envisioned and maybe could have been sharper and more interactive. Yet it felt authentic, organic, and successful. Sharing her stories, Anna gave students a glimpse of the joy and depth of learning languages and connecting with people across countries and cultures. Maybe something she said or suggested will shape their their future studies or careers, or influence their attitudes and way of being in the world. Ojalá.

Over lunch, Anna and I trade stories about our spouses, children, and summer plans. At one point, she mentions My Brilliant Friend, which we agree is one of the best novels ever written. The story centers on the friendship between two women in Naples. Along the way, the novel contrasts the working class Neapolitan dialect with the (Tuscan) Italian of the intelligentsia, illustrating how language can bring people together and tear them apart.

Like Lenú and Lila, Anna and I met as kids, bonded over a shared sensibility, and remained friends for decades. And while we’ve never clashed as dramatically as the Neapolitan friends or even ever really argued, today’s anxiety suggests some aspect of our relationship can trigger some of my insecurities and self-doubt.

I will never be a native Spanish speaker like Anna. But I’m happy she visited my class and thrilled that our friendship now has a new shared language.