On Friday afternoon, I bike north along the Hudson River in Manhattan. In the heat, I’m sweating through work clothes: navy blue shirt, charcoal pants, and slate grey shoes, plus a canary yellow helmet and sunglasses from a recent adventure in Cuba.

Today I’m riding uptown to swim with a friend in Harlem. Last summer, we swam together across the Hudson, along with another friend, 100 kayaks, and 200 strangers. This summer, I’ll be participating in my first triathlon. I’m excited, but also anxious.

The paved path is car-free, but busy with walkers, joggers, and runners. Sporty cyclists in spandex whip past on sleek bikes. Delivery guys zoom on electric bikes toting food-filled backpacks. Casual riders in street clothes wobble on CitiBikes, as they check their phones. To the left, boats churn the sun-dappled water. To the right, cars and trucks clog the West Side Highway. In the distance, the George Washington Bridge looms, a grey gateway to New Jersey—and the rest of America.

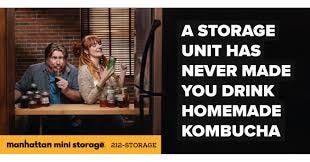

I bike past Chelsea Piers, the sprawling sports complex, the Frying Pan, a docked boat that serves fried food and beer, and terminals for helicopters, ferries, and cruise ships. One billboard beckons: Eat tacos on a boat. Another quips: A storage unit has never made you try their homemade kombucha.

On the Upper West Side, a guy drives golf balls in an otherwise empty baseball field. Two teen boys kick soccer balls into a goal. Boys and young men play basketball, another reminder of Cuba. Middle-aged men and women play pickleball on paved courts and tennis on red clay courts, a quasi country club embedded in a public park. Once a post-industrial wasteland, the waterfront path—aka the Hudson River Greenway—is now an athletic artery, a palpable sign of the city’s health.

Obsessive city cycling

Biking along the river lifts my spirits with adrenaline and memory. I work in Manhattan, but haven’t cycled in the city in five years, not since we left Brooklyn and moved to the suburbs in the pandemic exodus.

Before that, I was an obsessive city cyclist, not for fitness, but for fun and freedom. For years, I biked everywhere, commuting by bike over East River bridges, looping laps in Central Park and Prospect Park, and riding with friends from Williamsburg to Bay Ridge, circumnavigating Manhattan, biking to the beach at Coney Island, Breezy Point, and the Rockaways. On weekends, we titled our urban rides with mock grandiosity: Tour de Queens. Tour de Bronx. Tour de Staten Island. We memorized and annotated the bike map of the city, constantly striving to find the fastest and most enjoyable routes from point to point.

We thought we were rebels, with single-speed bikes and U-locks tucked in belt loops, bragging how riding was faster than the subway, more sustainable than driving the cars we did not own, and cheaper than cabs we could not afford. We also thought we were invincible, not wearing helmets and biking home from bars in the dark after drinking. Thank God nobody got hurt.

Now, the bike path ends abruptly, apparently closed for construction. I still have 50 blocks to go about two miles. A young couple stops behind me, also baffled. A Parks department employee suggests we carry our bikes up two sets of steep steps, then continue north on Riverside Drive.

The CitiBike is bulky and weighs 45 pounds plus my bag with a laptop, notebooks, and a paperback copy of Valeria Luiselli, Los Niños Perdidos, about the novelist’s work as a translator and interpreter in New York City for undocumented Spanish-speaking children who migrated alone from Central America to the United States, seeking asylum and facing deportation. When the book was published in 2017, I read the English translation, Tell Me How It Ends. A few years ago, I read the original Spanish, which I now teach as part of an exploration of the American Dream from the perspective of Latin America. This morning, students in my class studied this section:

If someone were to draw a map of the hemisphere and trace the history of one child and his individual migratory route, and then the route, of another and another child, and then the dozens of others, and then the hundreds and thousands who preceded them and will follow them, the map would collapse into a single line—a crack, a fissure, a wide continental scar.

Long before Luiselli was dubbed a MacArthur Genius, I admired her work as a writer with a social conscience, someone who uses her linguistic gifts to make the world a better place. In any language, Tell Me How It Ends feels as urgent in 2025 as it did nearly a decade ago, as the nation continues to wrestle with the immgration “crisis” and deciding who gets to be an American—and why.

Riverbank Renaissance

At the top of the hill, I pause, panting. Then I ride on Riverside Drive to 145th street, where my friend is waiting on a bench in a floral shirt, fedora, and sunglasses. We met in college, two gaijin studying Japanese. Now, we cross into Riverbank State Park, a massive sports complex built on a sewage plant that on hot days you can smell for miles. The park’s origin story is paradoxically heartwarming and heartbreaking.

In 1993, New York State opened the gates of the twenty-eight-acre Riverbank Park on the Hudson River in West Harlem. Built atop the City's North River Wastewater Treatment Plant, the park was designed to provide a measure of environmental justice by providing the community with a public space for recreation and community engagement in return for placing a wastewater treatment site in the neighborhood. With sweeping views of the George Washington Bridge and the Hudson Palisades, this park is situated at, arguably, one of the most beautiful sites in all of New York City.

At the entrance, we pass Sofrito, a Puerto Rican restaurant featuring a window full of liquor bottles, and a patio with a majestic river view. At the well-kempt running track, I recall the only other time I’ve been to Riverbank: at a school track meet. In the esplanade, cherry trees bloom near a forest green placard pointing to the Pool/Piscina.

We enter the pool complex, get changed, and swim. The lanes are literally labeled slow, medium, and fast with yellow plastic placards, but everyone in the water seems to be swimming at the same slow-medium pace. My friend takes the “fast” lane. Rather than share space with him–a tall, broad bro with a manspreading breaststroke, I choose an empty “medium” lane and swim solo.

The water is warm. I swim freestyle, then cool down with a green kickboard that says Learn to Swim, presumably gear from the government swim program. Last summer, Gov. Kathy Hochul was here at Riverbank, where she announced that the state:

…is waiving swimming pool entry fees at New York State Parks this summer. Additionally, Governor Hochul launched the $1.5 million Connect Kids to Swimming Instruction Transportation Grant program to help with transportation to swimming lessons as part of the NY SWIMS initiative. This follows the Governor's historic $150 million NY SWIMS investment to support pools in underserved communities – New York's biggest investment in swimming since the New Deal.

Swimming at Riverbank makes me proud to be a New Yorker, a state where access to pools, swimming, and water safety is not a privilege reserved for the elite, but a right for everyone. Or at least that’s the ideal. Hochul’s program is a good start–and also a drop in the bucket. The state, city, and country could invest millions more in pools, lessons, and lifeguard training.

Leaving the pool, I spot a sign on the wall that celebrates the members of the local swim team, with their names listed beneath three flags, all red, white, and blue: Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and the United States.

After the swim, I have three spontaneous Spanish conversations: one with the woman at the pool reception desk, a second with a guy on the field who takes a photo of me and my friend and a third with the proprietor of a taco truck with the uplifting name of La Viagra. Unlike me, they are native speakers. But so what? Our exchanges remind me that the point of learning a language is not perfection, but connection.

In the Disney movie Luca, an “Italian triathlon” entails biking, swimming, and eating pasta. While my late Italian grandmother might take offense, I prefer today’s version of a West Harlem triathlon: biking, swimming, and eating tacos.

Across 125th Street

After lunch, I bike south, pause to admire Riverside Church, then cut east across 125th street. The crosstown trip is not for the faint of heart. There’s no bike lane and the street is clogged with cars, trucks, buses, taxis, motorcycles, and scooters, all jockeying for position and swerving to avoid all the double-parked vans and delivery trucks and rogue pedestrians. Meanwhile, music is blasting from car windows, storefronts and sidewalk speakers–amplifying the adrenaline, a throwback to city cycling past.

At an intersection, a trio of teenagers jaywalk ten feet in front of me. I can’t brake fast enough, so I speed up and swerve around them to avoid a collision. Amped and aggravated, I glance over my shoulder, and shoot them a disapproving look.

“Keep going,” one girl shouts, laughing. “Pedal faster.”

Briefly, I’m annoyed at their arrogance and embarrassed to be the object of ridicule. Then I remember they’re just kids, the center of their own universe, who still think they’re invincible, the way I felt way long past adolescence, probably way too long. How many close scrapes did I avoid? How many dances with death?

I’m no longer a reckless Brooklyn bike bro, but a responsible suburban family man. Still, I’m not quite ready for a rocking chair in a retirement home.

I stand up, lean my weight into the pedals, and speed down the city street.